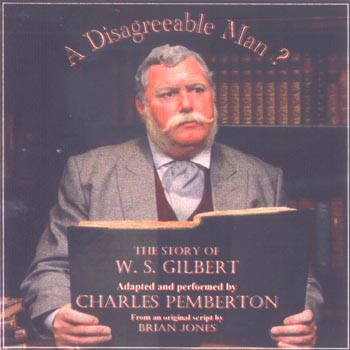

A Disagreeable Man?

This is a studio recording of Charles Pemberton's one-man show on the life of W. S. Gilbert. I once had the pleasure to see it live (at the International Gilbert & Sullivan Festival). Pemberton died a couple of years later, but fortunately he is survived by this souvenir of the show.

The production was formerly available on the Sounds on CD label, and my comments below refer to that version. That version was withdrawn, and Pemberton later issued another CD, apparently of a different performance. Pemberton has since died, and at this point it seems that neither version is available.

CD Cover |

The piece begins arrestingly with a recreation of Gilbert's death, and the rest of the show takes place somewhere between this world and the hereafter, with Gilbert apparently offering an apologia for his life. As the liner notes observe, the question mark in the title reflects the ambiguity in Gilbert's character: was he really so disagreeable, or not?

Pemberton animates Gilbert vividly, and many of the words used are the librettist's own. But does it "feel" like Gilbert? To my ears, it falls a bit short. Part of the problem is that Pemberton seems to take too much delight in recounting anecdotes in the character's life, but by most accounts the real Gilbert was rather reserved when it came to talking about himself.

Brian Jones is credited as author of the playscript, and as one would expect the quality of the scholarship is superb. The play is in two acts, and the break falls between Pirates and Patience. This division allows Pemberton to explore Gilbert's early career at leisure, but in the second half a lot of important events seem to go by too quickly.

None of us can know for sure whether Pemberton is a believable Gilbert, but he is certainly entertaining. As spoken-word CDs go, this is one of the more enjoyable ones you'll come across.

After reading the above review, Brian Jones added the following:

As the writer of the show, I saw the performance at Grims Dyke on the evening of 29th May 1999. Charles Pemberton does indeed look very like W. S. Gilbert. The dining room (Gilbert’s drawing room) contains a bust of Gilbert, and people in the audience who were not particular Gilbertian enthusiasts remarked spontaneously after the show that Charles did indeed look like the bust, and I can assure you that Charles is suitably animated.

Marc asks whether the characterisation is authentic. Could the Disagreeable Man really take so much delight in recounting the events of his life? Gilbert’s acquaintances — critics, rival dramatists, underachieving thespians, adversaries in court — did not find him a friendly conversationalist. He could be formidable. He could also be precisely the opposite. I have looked at several accounts from people he entertained at his parties. On these occasions, Gilbert was pleasant, charming, funny and agreeable. Nor was the fun invariably at someone else’s expense.

The evening of the performance at Grims Dyke came at the height of the rhododendron season. Of all the flora that Gilbert brought to Grims Dyke, he was proudest of these flowers. The evening, of course, was an exact anniversary of his death. As I watched the performance, the wide windows of Gilbert’s drawing room were ablaze with solid pink. I felt that the stage manager in Gilbert would especially have enjoyed that particular seasonal setting for his final scene.

Sounds on CD VGS218 [discontinued version] |

Review by Robert Morrison

Having heard the Sounds on CD recording of the one-man show "A Disagreeable Man?" I would like to congratulate Charles Pemberton on his excellent portrayal of W. S. Gilbert, which I personally believe is the most well-rounded, believable and accurate portrait of the great man that we are likely to get from someone who isn't W.S.G. himself.

Everyone who knew W. S. Gilbert personally, or had personal dealings with him, had their own perspective on what type of person he was. And so every person who only knows of W.S.G. second-hand from biographies and other such written sources has only an incomplete two-dimensional interpretation on which to base their impressions of what he was really like as a three-dimensional living, breathing man. This is comparable to the manner in which readers of the, albeit fictional, Sherlock Holmes stories form their own personal conception of what the famous resident of 221B Baker Street is really like — by fleshing out the bare bones of Conan Doyle's word-pictures from their imaginations.

Two people who knew Gilbert better than most were the British actor/manger Seymour Hicks and his actress wife Ellaline Terriss, who were regular guests at W.S.G.'s country home "Grimsdyke" between 1894, (when Terriss played the role of Thora in Gilbert's production of His Excellency), and 1910. (Terriss, in fact, was a distant cousin by marriage of W.S.G.'s and this 'family connection' helped to initially establish and promote his friendship with the couple.)

In his second book of memoirs, Between Ourselves [Cassell & Co., London; 1930], Seymour Hicks observed that "Gilbert always had the greatest contempt for critics and disliked journalists as a body intensely," and so to such people he was terse, flippant and reserved when talking about himself. Conversely, "being a great admirer of pretty women he took endless trouble to amuse them," and so to such women he was witty, personable and charming.

In her first volume of autobiography Ellaline Terriss — By Herself and with Others [Cassell and Co., Ltd., London; 1928], the authoress wrote:—

Seymour and I had the pleasure and good fortune on many occasions of being the guests of Lady Gilbert and Sir William at their country place, Grimsdyke, near Pinner, and it was a delight to listen to him, and I am sure a greater delight for him to be listened to. At table he was not so much a conversationalist who caught the ball and passed it on, as a teller of witty stories connected with himself.

While Hicks observed (in Between Ourselves, pp. 49-50),

[M]ost of the stories he told were of personal grievances, the battles they had caused, and the verbal victories that he had won, but I'm bound to say that the constant repetition of his passages-at-arms and the stock jokes he indulged in, while being amusing at first, became very like one of his own flashes when someone said to him, "Mrs. So-and-so was very pretty once," and he replied, "Yes, but not twice."

Likewise W.S.G. was a gifted mimic who, according to Terriss (in her second book of memoirs, Just a Little Bit of String [Hutchinson & Co., London; 1955], pg. 114), "could show everybody exactly how he wanted a part played; it did not matter if they were male or female, he would give them the exact movement and intonation. And considering that he was a giant of a man, to show a young pretty girl how she was to move and speak — and to do it perfectly — was certainly something."

Hicks and Terriss would then consider Charles Pemberton's portrayal of W.S.G. to be the great dramatist "to the life." (Hicks also had the misfortune to experience the other side of W.S.G.'s personality when, in 1910, the dramatist offered the performing rights of Ruddigore to him and his producing partner Charles Frohman, with the suggestion that George Grossmith's part would suit Hicks "admirably." Both producers, however, lacked the necessary capital to undertake staging such a costly production and so Hicks, though honoured, regretfully declined the offer. W.S.G. interpreted Hicks's refusal as an outright rejection on the grounds that Ruddigore had been a "failure" on its first production at the Savoy. Hicks tried to point out that this was not the case, but W.S.G. would have none of it and stormed off in a fit of pique. Thereafter, although he frequently met up with him at the Garrick Club, W.S.G. never again spoke to Hicks, and Hicks deeply regretted that the rift remained unhealed at the time of Gilbert's death in 1911.)

In his excellent biography Gilbert and Sullivan [Hamish Hamilton Ltd., London; 1935], Hesketh Pearson observed (on pp. 268-9) that:—

Few men can have left such widely different impressions on their contemporaries as Gilbert did on his. Some people, especially women, thought him pleasant, simple, kindly, affectionate. Others, mostly men, found him overbearing, intolerant, conceited, offensive. The truth seems to be that he was instantaneously irritated by self-important folk, by those who thought a lot of themselves and gave themselves airs. There was no humbug about him; he hated anything in the nature of a pose; his manner was abrupt and direct; and he never went out of his way to make people feel comfortable. The consequence was that he was feared and hated by anyone whose vanity he had pricked, and as he saw a good deal of absurdity in everybody and everything, the only human beings who got on well with him were those who had no exalted opinion of themselves. He had an essentially critical mind; he believed in nothing. It would be possible to prove from his works that he was a socialist, a conservative, a cynic, a sentimentalist, a monarchist, a republican, a reactionary, a revolutionist. In fact, apart from his satirical genius and business acumen, he was a typical easy-going, unadaptable, independent, disrespectful, prejudiced, grumbling Englishman, who scorned everything he did not curse, accepted the conventions and made fun of them. He was cantankerous in manner and generous in deed. His sentimentality was screened with bluster. While looking at the face of a friend who had just died, he burst into tears, rushed from the room, pounded down the stairs to the accompaniment of loud oaths, seized the butler and bellowed wrathfully: "George, have you seen my bloody umbrella?"

Elsewhere in the book (pp. 36-7), Pearson notes:—

We shall find that Gilbert, at the end of his life, did his best to patch up ancient quarrels and to disown the many acid sayings attributed to him. He succeeded so well that many of his most famous gibes are now commonly regarded as apocryphal. But the mellowing picture of an ageing man, anxious above all things to conciliate his contemporaries and to leave the world in an odour of charity and good-will, must not be accepted as an accurate representation of the younger man whose restless desire to achieve pre-eminence set him at odds with all who would not bow to his will and whose jealousy of the success of others expressed itself in a wit that cut like a whip. There is quite enough authentic evidence for the truth of his recorded sarcasms to justify their inclusion in the most prudent biography.

Pearson's observation about the mellowing and ageing Gilbert is consistent with Charles Pemberton's portrayal of W.S.G. on the day of his "death" as a man who is attempting to make an accounting of his life "as a whole" to the "recording Angel" by displaying all aspects of his personality, including his wit, his kind-heartedness, his sentimentality, his flirtatiousness, his pontificating and his flashes of (self-justified) temperament and anger. I congratulate Pemberton on his adaptation of Brian Jones's script, which gave him an appropriate framework in which he could achieve this. (But I would suggest that, perhaps, he really ought to acknowledge Hesketh Pearson as well for the invaluable collaborative "assistance" that he gave with some of the "Gilbertian" dialogue and observations from his biography!)

Who exactly was the "real" W.S.G.? The question is unanswerable, because he presented a different aspect of himself to different people. And for the same reason the implied question in the title of "A Disagreeable Man?" is equally unanswerable. (Like all official utterances!)

Nowhere is this dichotomy in Gilbert's true nature better illustrated than in his creation of the characters of Robin Oakapple / Sir Ruthven Murgatroyd, the "bad" baronet of Ruddigore and his brother Despard. Robin is a man who, on the one hand, "loves a little maid" and is "as timid — wretched — bashful as a youth can be," but on the other is a swaggering braggart who announces to Richard Dauntless that "you must stir it and stump it and blow your own trumpet, or trust me you haven't a chance." He is likewise a man who tries to make a show of being the wicked baronet Sir Ruthven Murgatroyd in the 2nd Act, but in his heart still remains the meek farmer Robin Oakapple. When Despard makes his entrance in Act 1, he is the "moody and sad — guiltily mad — thoroughly bad" baronet of Ruddigore, but by the 2nd Act he has transmogrified, (together with the former "Mad" Margaret), into the proprietor of a National School who "only cut[s] respectable capers" and is a "dab at penny readings."

To the actors portraying the multiple personalities of the roles, who then are the "real" Robin Oakapple/ Sir Ruthven Murgatroyd and the "real" Despard Murgatroyd? The answer is that all are different aspects of the same characters. So it was with the "real" W.S.G., whose personality was equally multi-faceted. Oakapple/Murgatroyd and Despard are just as much reflections of W.S.G.'s "public persona" as the characters of King Gama and Jack Point are said to be. Perhaps we could even argue that the Murgatroyds are Gilbert's own personal version of The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, as R. L. Stevenson's celebrated novella was first published in 1886, while Ruddigore premiered at the Savoy the following year.

Views of W. S. Gilbert for more extensive quotes from the books by Seymour Hicks and Ellaline Terriss.

| Date | Label | Format | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Sounds on CD | CD | VGS214 |

| 2004 | privately issued | CD | [not numbered] |